Image 1 of 19

Image 1 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 19 of 19

Image 19 of 19

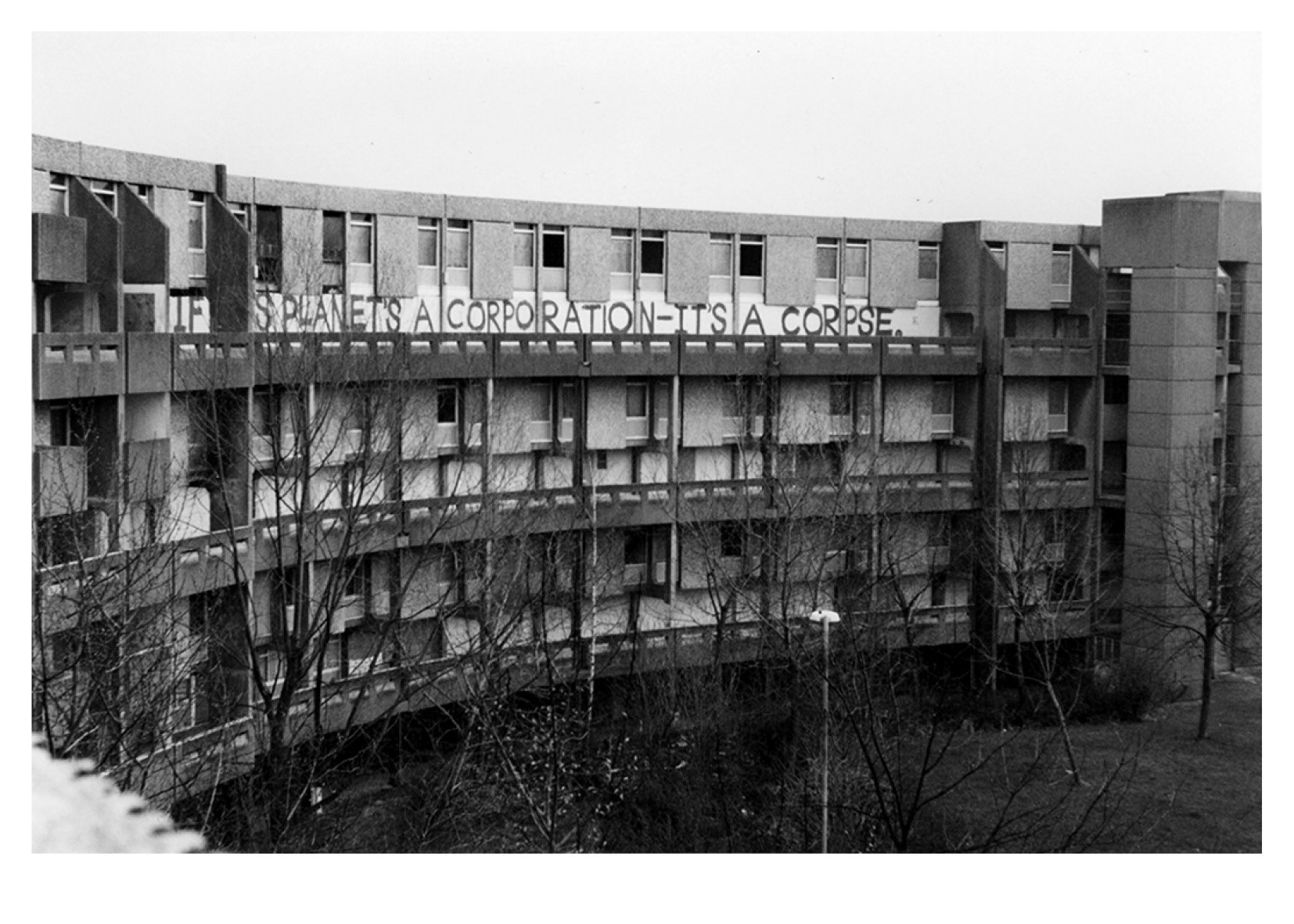

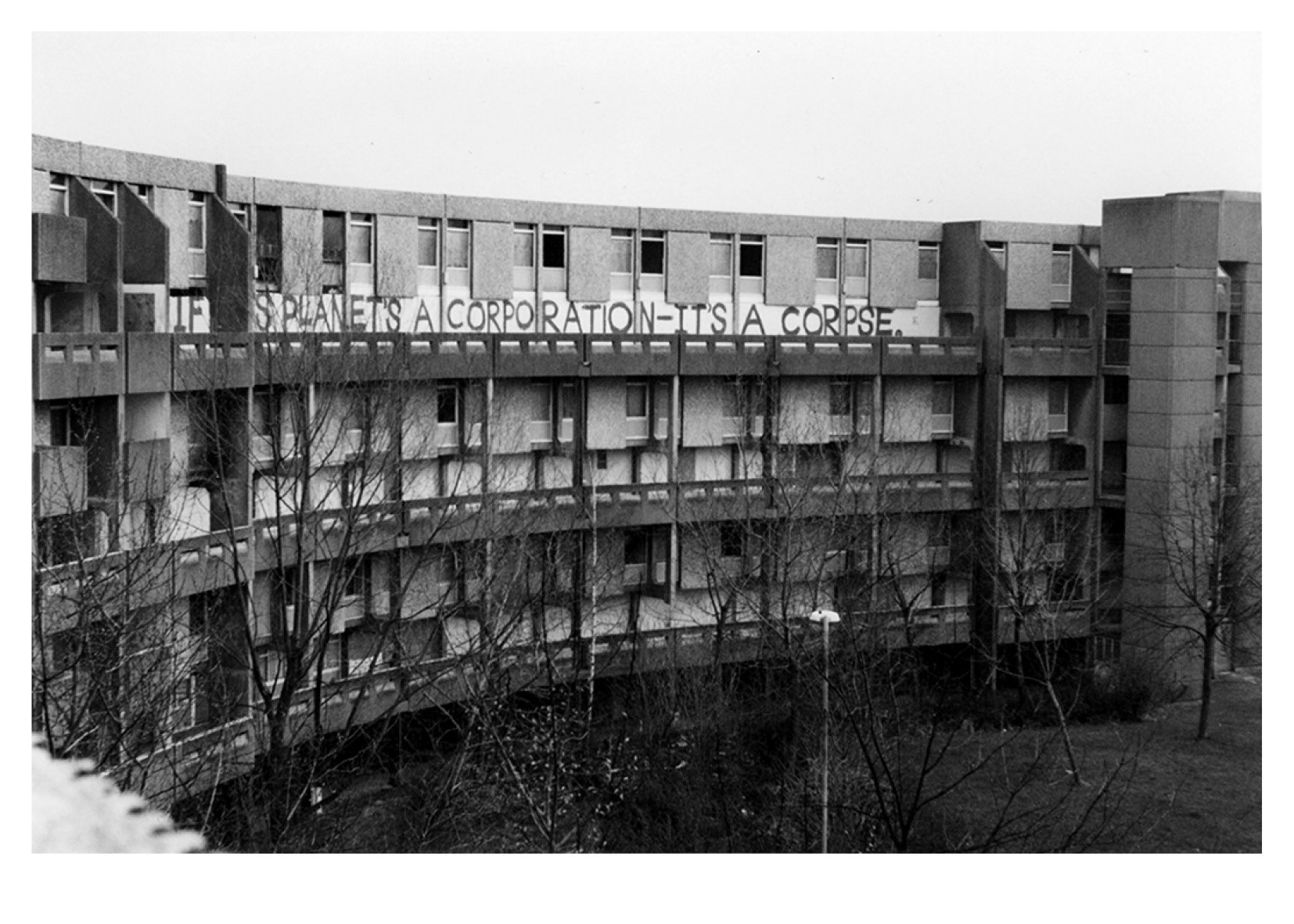

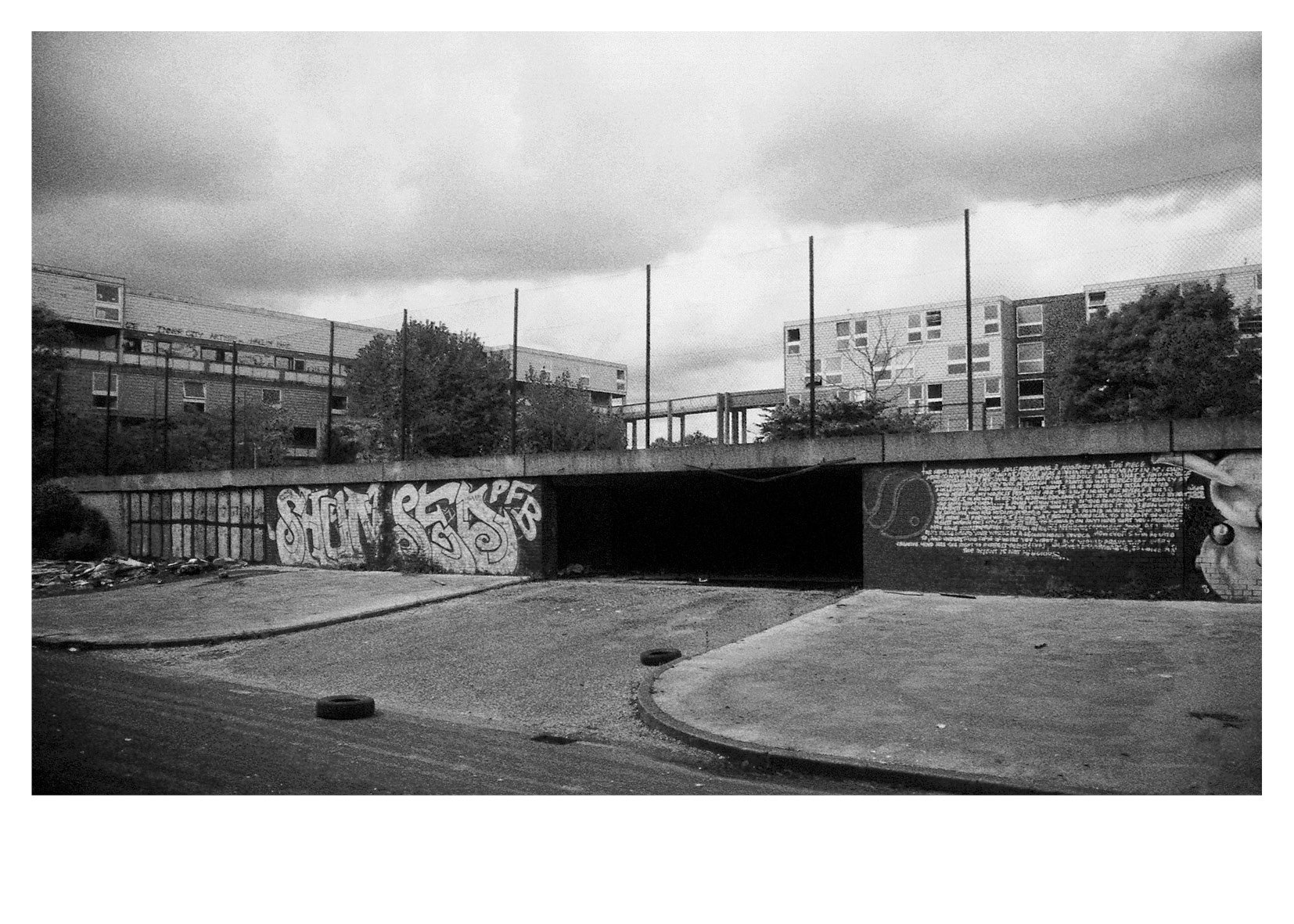

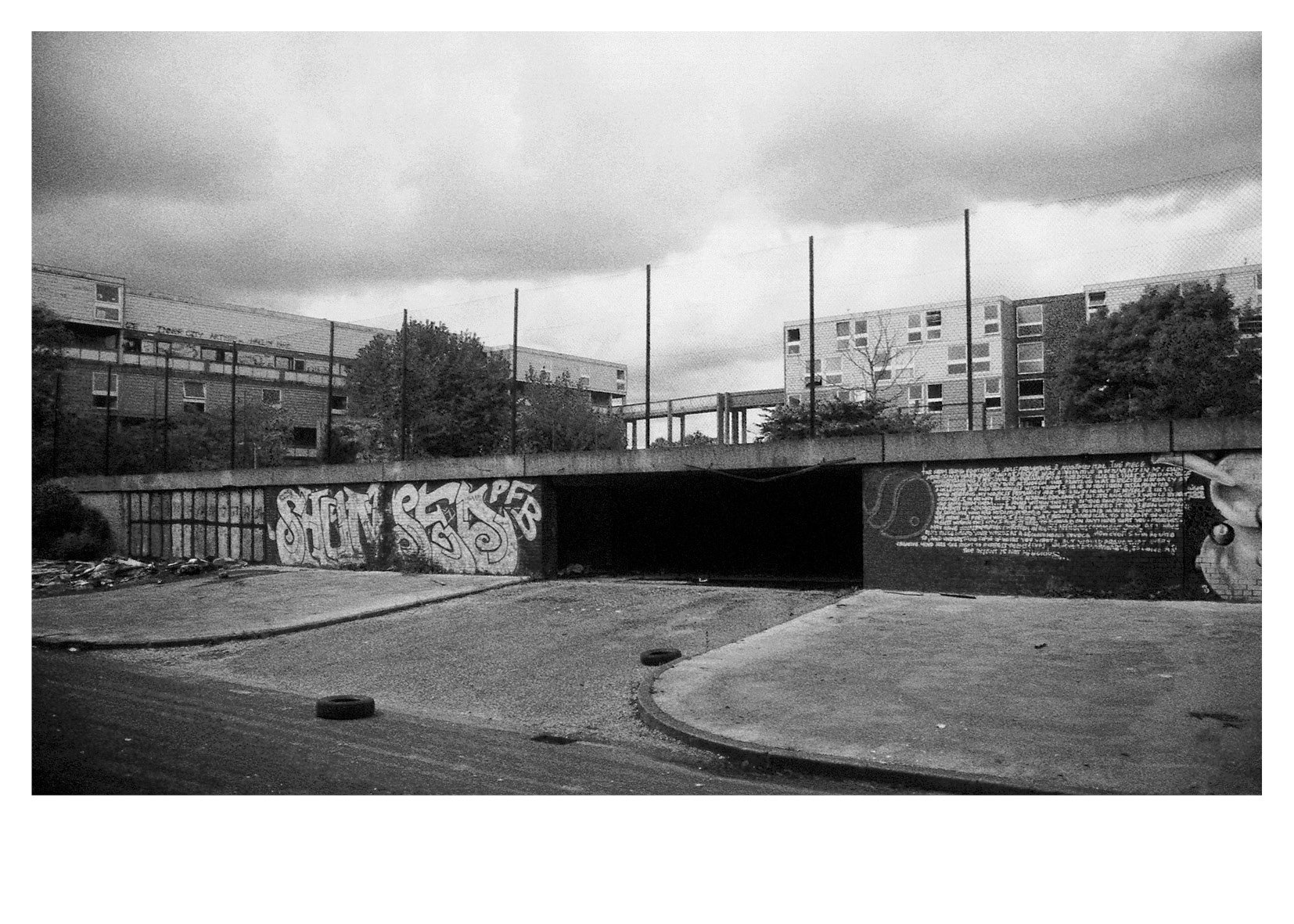

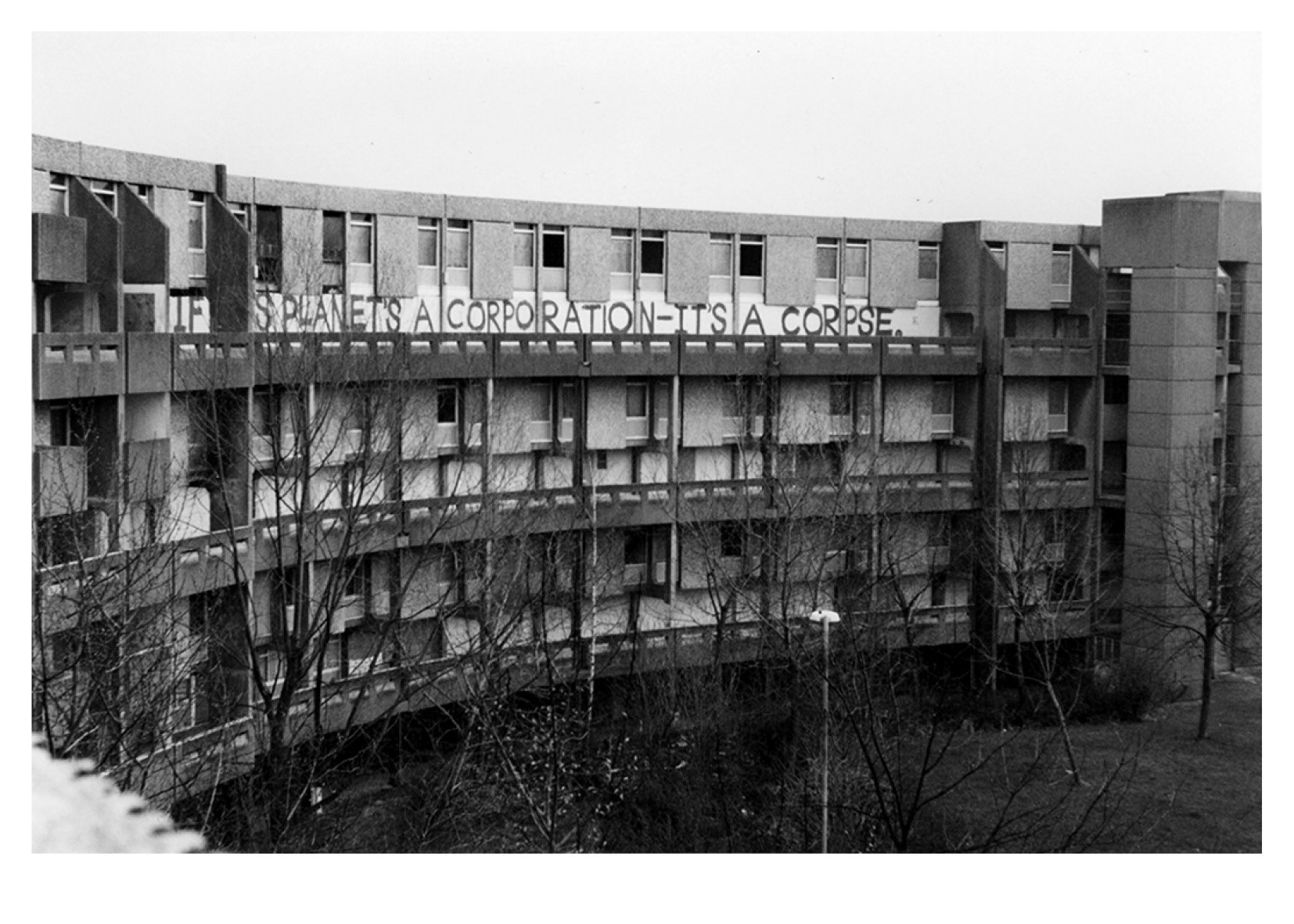

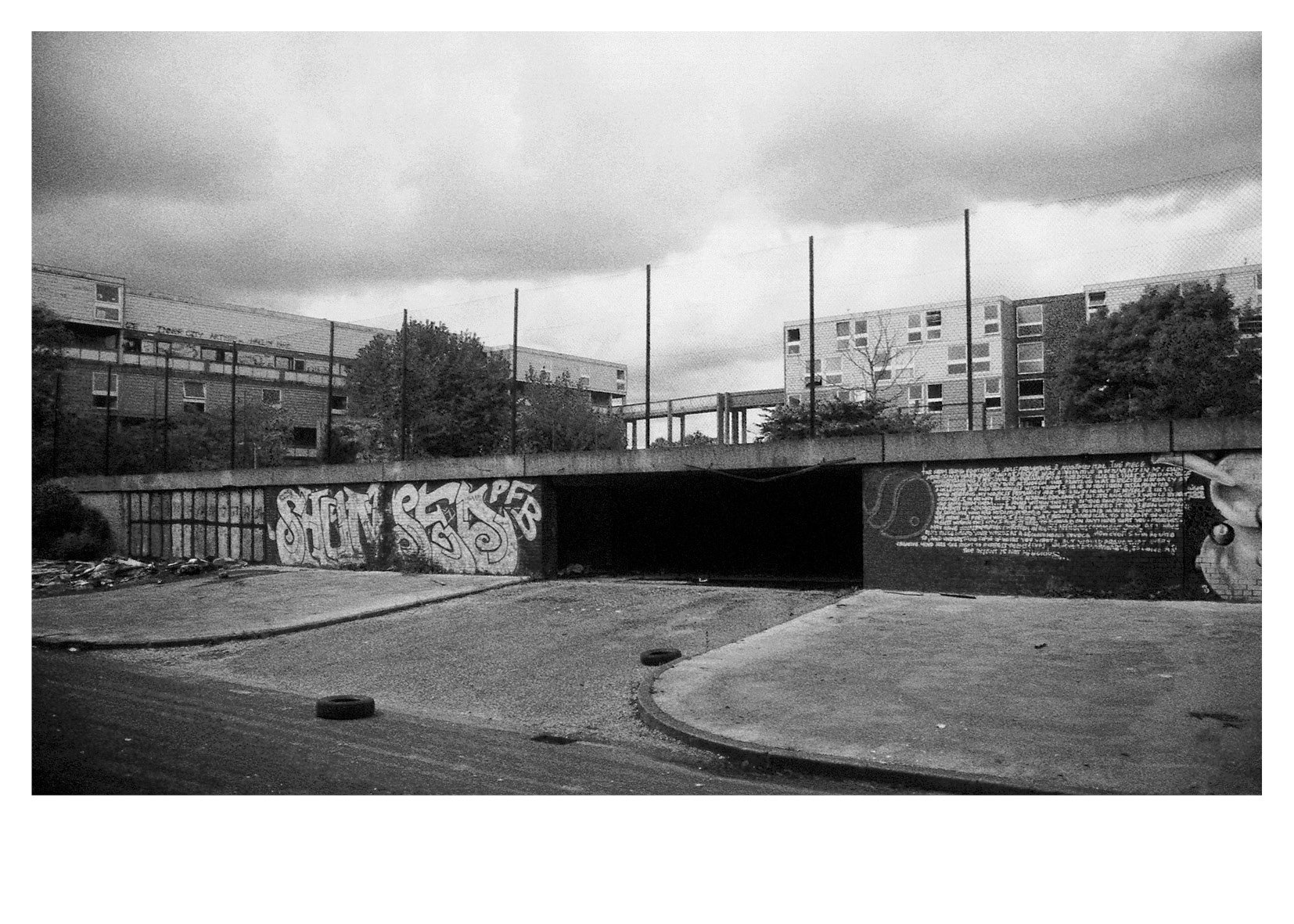

Anne Worthington — Hulme 1993

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

I lived there for a few years from 1989–93. I went to a party there one time and knew there was something in that place for me, and that I’d have to live there to find out what it was. Sounds daft but that’s exactly what happened. You’ll know all too well that Hulme was like a republic in the 1980s and early 90s, a law unto itself, and a beacon for all this love and rage that couldn’t find a voice elsewhere, not in that political climate anyway. I guess art was our way of fighting back, we used it as a strategy because we were learning that it transmitted more loudly and widely than our voices could.

No one could hold back a book, or a club night, or a track people loved to dance to. I was a girl from Blackpool, and Hulme was my one chance and I couldn’t afford to mess it up. I was part of Dogs of Heaven, a collective that produced outdoor spectacles — part punk, part circus, part ritual, every performance involved fire.. We usually did something to mark an occasion. We built a 40 ft Wicker Man made out of raided staircases from Crescent flats, took it down in lorries and burnt it at Glastonbury Festival. And we built a 40 ft Viking ship with wood from the same places, and the audience pushed it down the streets without a road block, all the way to William Kent Crescent where we burnt it for Bonfire Night. We did a number of these things around the country, and by the end, they were getting a fair bit of attention but we were hardly speaking to each other. We were over a hundred in number by then and they were hard shows to put into action, dangerous as well, but I guess that was part of their appeal. The last time we came together in 1992, we did a live demolition show to mark the end of the Hulme crescents. At the very end, we threw cars off the roof. There was no way of rehearsing it, we just had to run with whatever happened on the night.

I taught myself photography after that, and what you’ve seen are my first photographs taken on a beaten up Praktika camera. I learned at the speed I could afford film, which was one film a month. I visited Waterstone’s photography dept a lot looking at the monographs, working things out with a magnifying glass. I couldn’t afford the books but I learned what i could by studying them. Later, I worked around the country as a documentary photographer. There’s so much to say about Hulme and the flats, what people did there, what was made there.. mums living in taxis with babies; someone lived in the lift for a while in William Kent. Flats covered in leaves, everything painted white, even the TV.. a flat that had no furniture and no front door that was guarded by two alsatians called Mr & Mrs Bridges; flats where there were mountains of cans and needles and dog shit and mattresses.. flats that were turned into recording studios, club spaces, party flats..

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

I lived there for a few years from 1989–93. I went to a party there one time and knew there was something in that place for me, and that I’d have to live there to find out what it was. Sounds daft but that’s exactly what happened. You’ll know all too well that Hulme was like a republic in the 1980s and early 90s, a law unto itself, and a beacon for all this love and rage that couldn’t find a voice elsewhere, not in that political climate anyway. I guess art was our way of fighting back, we used it as a strategy because we were learning that it transmitted more loudly and widely than our voices could.

No one could hold back a book, or a club night, or a track people loved to dance to. I was a girl from Blackpool, and Hulme was my one chance and I couldn’t afford to mess it up. I was part of Dogs of Heaven, a collective that produced outdoor spectacles — part punk, part circus, part ritual, every performance involved fire.. We usually did something to mark an occasion. We built a 40 ft Wicker Man made out of raided staircases from Crescent flats, took it down in lorries and burnt it at Glastonbury Festival. And we built a 40 ft Viking ship with wood from the same places, and the audience pushed it down the streets without a road block, all the way to William Kent Crescent where we burnt it for Bonfire Night. We did a number of these things around the country, and by the end, they were getting a fair bit of attention but we were hardly speaking to each other. We were over a hundred in number by then and they were hard shows to put into action, dangerous as well, but I guess that was part of their appeal. The last time we came together in 1992, we did a live demolition show to mark the end of the Hulme crescents. At the very end, we threw cars off the roof. There was no way of rehearsing it, we just had to run with whatever happened on the night.

I taught myself photography after that, and what you’ve seen are my first photographs taken on a beaten up Praktika camera. I learned at the speed I could afford film, which was one film a month. I visited Waterstone’s photography dept a lot looking at the monographs, working things out with a magnifying glass. I couldn’t afford the books but I learned what i could by studying them. Later, I worked around the country as a documentary photographer. There’s so much to say about Hulme and the flats, what people did there, what was made there.. mums living in taxis with babies; someone lived in the lift for a while in William Kent. Flats covered in leaves, everything painted white, even the TV.. a flat that had no furniture and no front door that was guarded by two alsatians called Mr & Mrs Bridges; flats where there were mountains of cans and needles and dog shit and mattresses.. flats that were turned into recording studios, club spaces, party flats..